'Chasing the Sun' exhibition by Marwan Rechmaoui at Sfeir-Semler Gallery - photos

ArtDayME: Sfeir-Semler Gallery in Beirut presents Marwan Rechmaoui's new solo exhibition "Chasing the Sun".

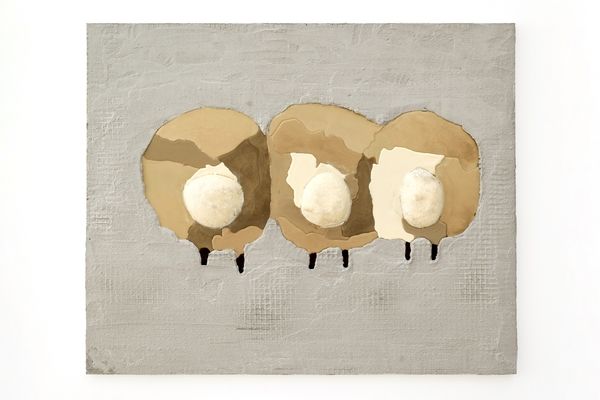

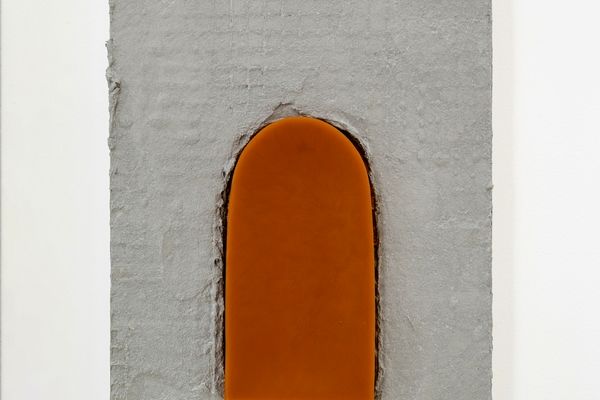

Marwan Rechmaoui is a conceptual sculptor who works predominantly with concrete, metal, rubber and wax. Continuing his inquiry into the socio-geographies of cities, Rechmaoui introduces a fresh body of work centered around the concept of play. Musing down memory lane, he examines the streets of Beirut through the lens of childhood games, prompting in the process multifold questions about the influence of toys on shaping societies.

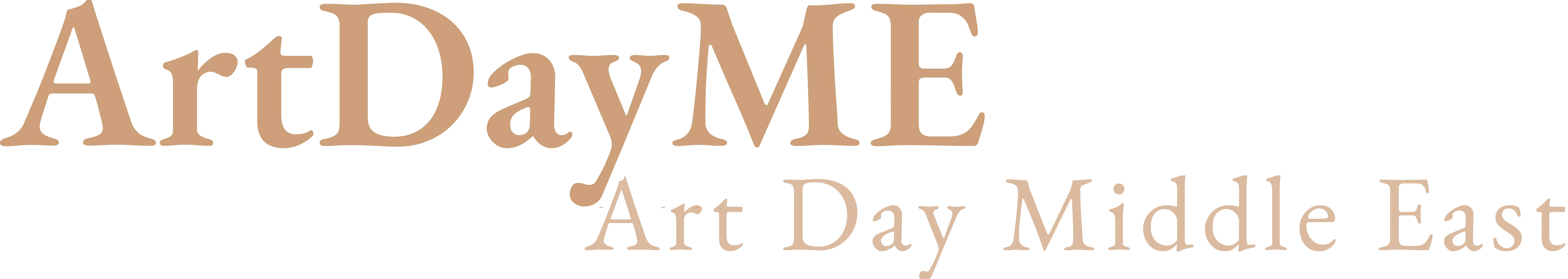

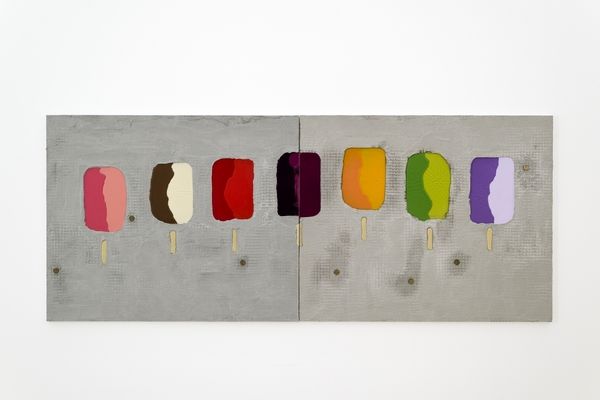

This concept isn’t new to Rechmaoui, who recently revisited a sketchbook from the 1990s in which he systematically recorded the games of his youth. Replicating these pastimes, he presents here a set of marbles, a kite, a hopscotch outline reproduced with oil pastel on concrete, or a sandbox with a throwing knife. The innocuous feel of these playful installations is reinforced by the works hanging on the walls: poetic representations of pine trees, flowers, cotton candy, ice cream sticks or clouds made with molten beeswax, mixed with colour pigments, and embedded in concrete.

Beneath this seemingly joyful atmosphere, Rechmaoui’s works propose a deeper social commentary inspired from Roland Barthes’ essay “Toys”, in which the author argues that toys are essentially a microcosm of the adult world. In other words, childhood play shapes adult identity. In this most recent series, Rechmaoui reflects on his own upbringing, and while he chases back these moments of untainted joy from his youth, he also draws connections between war and play. Suggesting that every game, by designating winners and losers, represents a form of symbolic killing of the latter, he presents several that harbor seeds of violence. Considering Lebanon’s context, it’s not difficult to link the games played by militia fighters during the Lebanese civil war and the ones they enjoyed in their youth.

At the level of their miniature worlds, children engaging in these activities often adhered to strict social hierarchies. The possession of a coveted toy (a ball, a bicycle, or even the inflatable tube of a tire used to float on water for example) placed one at the apex of the social order. Those displaying exceptional speed, strength, or intellect also ascended the hierarchy. This enduring culture of competition ingrained in childhood experiences persists today, despite the evolution of games in the digital age, and still translates into our stratified societies.

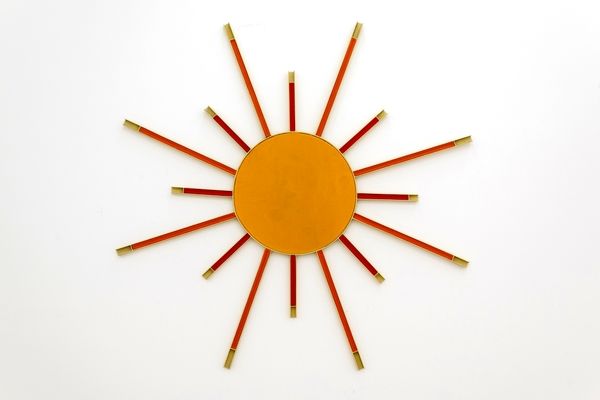

While manufactured toys were prevalent in many places, Rechmaoui’s childhood games were often improvised. Whether stacking seven stones, crafting a makeshift cart from salvaged wood, or drawing a checkerboard on the sidewalk to challenge a friend to a game using recuperated bottle caps, Rechmaoui’s playground, overlooked by his wax and concrete bright sun, tell us that the essence of play transcends materials. No matter what is used, whether handcrafted, traditionally made, or mass-produced toys, play remains a universal language, enabling children regardless of where they come from, regardless of the context or era in which they are growing, to communicate and understand one another.

"Chasing the Sun" exhibition continues until July 20, 2024

LEAVE A RELPY